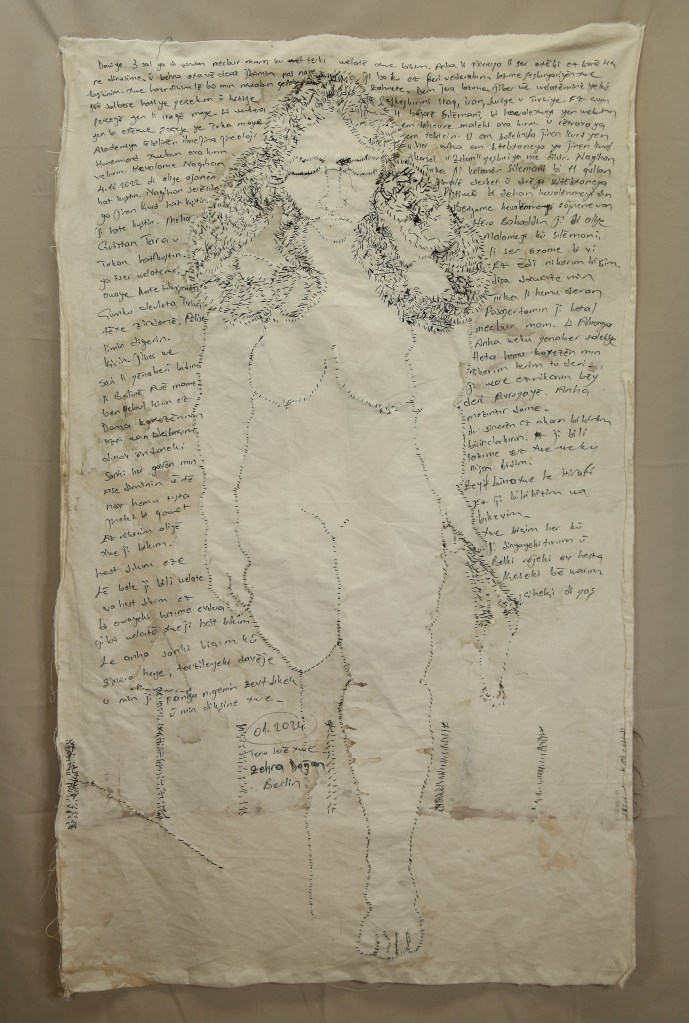

ALONE

After one year of war and three years in prison, I finally had to leave my country. Today I live in exile in Europe, in Germany to be exact, a country I’d never known before. Even the smell of this country is foreign to me. It will take me some time to get rid of my prejudices and my shell and to get used to it. 100 years ago Kurdistan was divided into four parts. I can’t go to the part that was given to Turkey, where I used to live. If I did, I’d be sent back to prison. Another arrest warrant has been issued against me, again because of my paintings and drawings. The police want to bring me back.

I can’t go back to Turkey, but I could stay in the Kurdish part of Iraq, which is also my country. So even though the part of my homeland that belongs to Turkey is off-limits to me, for the time being I could walk along its borders and breathe in the scent of the land where I was born, through barbed wire and minefields. So I went to the city of Sulaymaniyah, a city in divided Kurdistan. Even though it has been given to Iraq, this land is still mine.

So, in 2020, in Sulaymaniyah, we met with revolutionary comrades I knew who had also come from the part of Kurdistan that was united with Turkey. Like me, they could not return safely to their country. So we built a kind of common house for ourselves.

In this house, we carried out the work of the Academy of Jinéologie, Women’s Sciences, which Kurdish women had been studying for years. We also founded the Xwebun Collective, which consists of Kurdish women artists. And in the premises of the collective, we began to create the Kurdistan Women’s Library, where everything produced by Kurdish women artists is archived, something that had never existed before.

But before a year had passed, this home that we had built with my friends was dissolved under terrible circumstances.

Turkish state intelligence had begun to monitor our academy, where we were researching women’s science and history, a history that had been lost and ignored for thousands of years.

On October 4, 2022, as our friend Nagihan Akarsel was walking to our new library, a man working for the Turkish state fired 11 shots at her, killing her in the street. Already under surveillance by the Turkish police for her academic work, Nagihan had been forced to leave Kurdistan in Turkey and settle across the border in Kurdistan in Iraq, where she laid the foundations for the Women’s Library. With Nagihan’s death, the common home we were building was destroyed. Then dozens of my friends were murdered in the streets of the city of Sulaymaniyah, again by Turkish agents. Just last month, it was two of my journalist friends, Gülistan Tara and Hêro Bahadin.

Today I am back in Europe. I can no longer even go to this country, which has become just as dangerous for me and in which I still feel a sense of familiarity. The Turkish state has now cancelled my passport and I am officially a refugee in Europe. But I still do not have the right to travel. I have been stuck in Berlin for a year now. Like a border violator, each of my steps is caught in the tangled barbed wire of this fragmented planet. In spite of everything, I have to be strong, I cannot reveal my weaknesses, even to myself, otherwise I would collapse. Wherever I go, I cannot get rid of the feeling that I come from another planet, as if I have been teleported. But it is as if my roots, the traces and imprints left in the country where I was born, are constantly calling to my nerve endings and pulling me toward them.

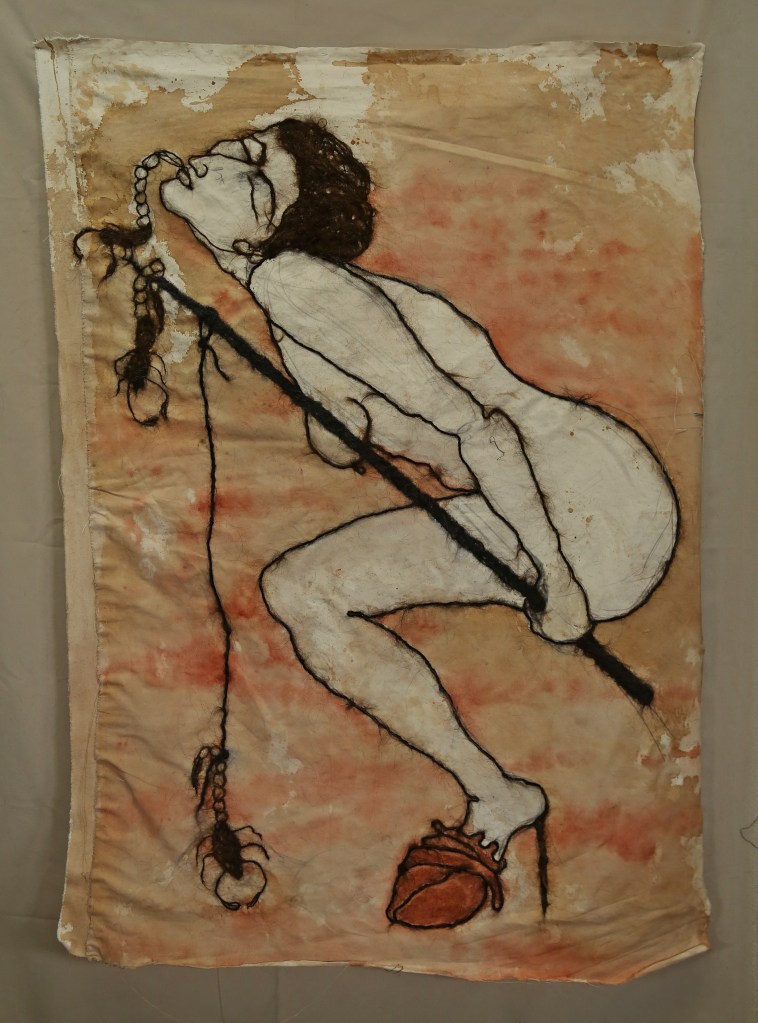

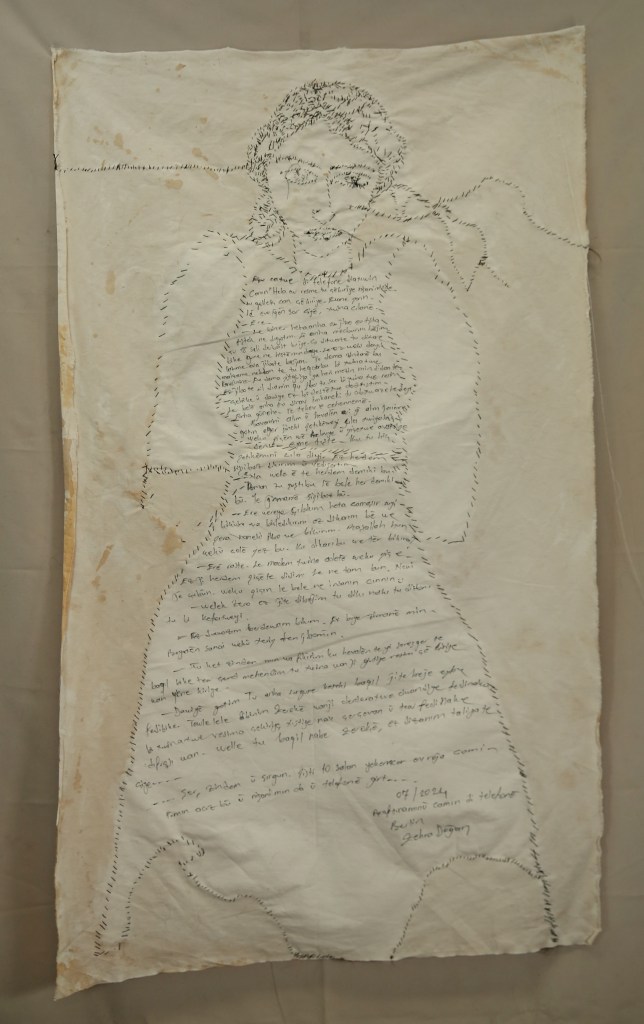

SCORPIO WOMAN

As I greeted my family members for the last time and said goodbye, this was about the last piece of advice my parents gave me face to face:

“Who knows when we’ll see each other again? You’ll be alone now. You’ve always been alone, but this time you’re really alone. You’re leaving for a continent you’ve never seen, for a life you’ve never known. And maybe you’ll never come back to your country, or find us when you do. Life goes on. A new battle, a new war begins for you, and this continent will be your biggest prison. Since you can’t go back to your house, it will be an open-air prison where you will be locked between borders.

Here the parties involved in the war are clear. The enemy and the people fighting the enemy. But over there, there are many scorpion nests with countless enemies hiding behind masks that you cannot even imagine. There is the main nest of scorpions that you drew in your work that brought you to prison. Try to recognize your friends and enemies well. Over there, there is no open war like here, and there are no barricades to hide behind. Therefore, you will not be able to stand up to them with the defense techniques you know; you will be defeated or lose your mind. They will throw you into the madhouse like a madwoman.

You must learn to observe and act with your heart. You are alone in this life, but if we, as your parents, have been able to give you the ability to feel consciousness, which is the name of the right connection between your mind and your heart, if you acquire this consciousness, you will not be isolated. You will be able to take care of yourself even if you are alone. Your awareness is your greatest weapon. The one who seems to be your enemy may have another face. Try to see his heart and soul. Do not immediately turn your back, even on your enemy, as long as you approach him with your awareness, you will be the winner.

You may never see us again. So let us tell you our last words. If we ever meet again, I am sure we will have different last words. But for now, remember this: you have always been strong because you knew exactly what injustices we suffer in this country, and you knew exactly what you were fighting against. If you find yourself fighting other things there, first know what you are up against. So good luck!”

Words from parents who had always seen their daughter at war and were sending her back to the front.

Diyarbakır/Kurdistan 2019

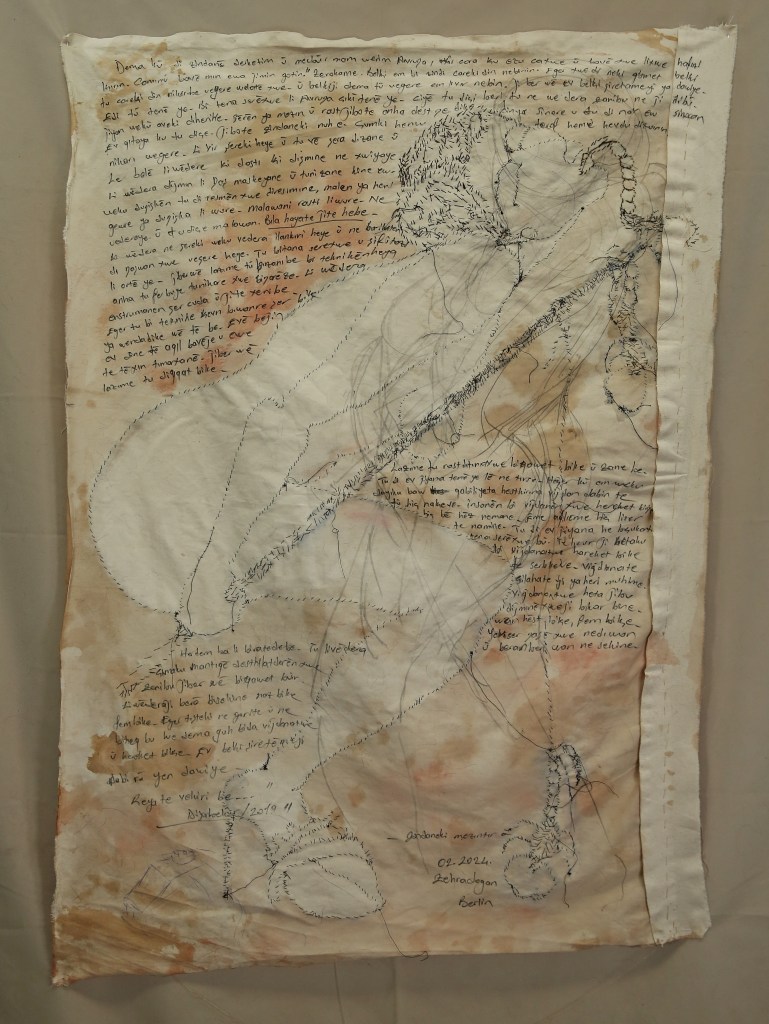

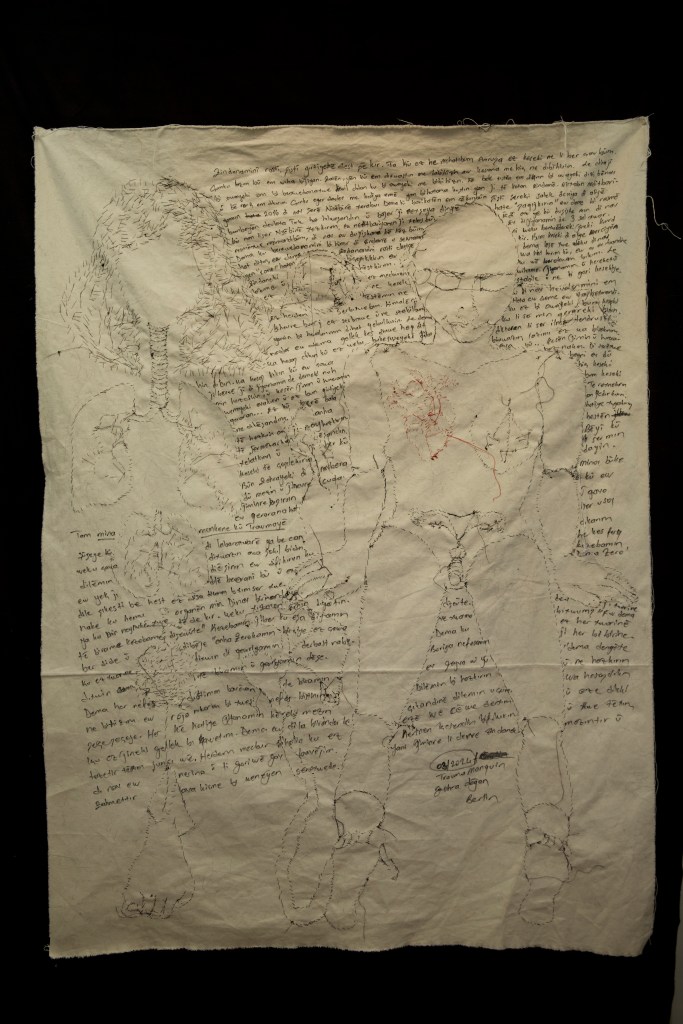

TRAUMA MANNEQUIN

I often write that my real imprisonment began after I was released from prison.

Before that, when I was younger, I lived in the shadows without being noticed too much. We had to live and work that way. Those who should have seen and heard us remained blind and deaf, but the desire to reach them made us fight. We had to be careful not to attract the attention of the State. If we became too visible, we risked being arrested or killed.

My “secrecy” ended during the war, in 2016, in Nusaybin.

After the demolitions, the barricades, and the destruction of the city, my invisibility was destroyed with a drawing I made. I was then in front of these scorpions that I had drawn and I found myself defenseless. This cost me 3 years of my life. But my real imprisonment began when I began to be seen only through the prism of my journalism and my art in prison, defined by my resistance through art. I then became a kind of public thing, appreciated by some, applauded by others, adored, rewarded…

To find myself in the realm of the “appreciation” of others meant that I had to go as far as they wanted me to go, but restrain myself so that the appreciation I received would never diminish. But I have an “unstable” life stability, I always behave spontaneously, according to my mood, my feelings of the moment, my maverick spirit. This time these facts put me between two fires, those who appreciated me and those who hated me.

I, whose personality no one was interested in before, because it had become visible, was transformed into nothing but a body, to be criticized, humiliated, hurt or weighed, rewarded and applauded.

Right in the middle of this division, a Zehra was fantasized by everyone in their own heads, without asking my opinion, lurching between love and dislike. Just like a boxing training dummy. Like a laboratory dummy, lifeless, to be shaped at will. As if everyone thought that if they hurt my heart, I would always be able to insert a new replacement heart without any emotion.

No one realizes that all my organs are already bruised. My insides, where I dig my nails, with the words of my relatives, “Our insides burn when we think of Zehra”… My oesophagus, torn by the pain of my mother, who leaves the table crying, “I can’t swallow a bite if Zehra is hungry now. » My father’s ears that remained deaf as long as he did not hear my voice. And this insidious pain in my windpipe that manifests itself every time I breathe…

And also these contractions that my mind creates all over my body because of this feeling of not belonging to any of the places I go, in this life of exile. My prison body that changes shapes, that twists and hurts me all the time…

GOAT

The newborn of our goat herd had gotten caught in the barbed wire that bordered the neighboring field. Its little leg was injured. I put him on my back and walked to the house. The heat of his body and mine quickly combined, creating a kind of balance. I could feel the beating of his frightened heart in the back of my neck. I was his rescuer, but I was also the one who would later slaughter him, skin him, cut him up, and eat him. I think that was exactly what his heartbeat made me feel. The purest feeling I had for him was: “I wish he would never grow up and he would always be this little child so that we would never have to slaughter him and eat him.“

A WOMAN IN THE GARDEN

I had a handful of rocks and a mouth full of curses. I had furrowed eyebrows and a high, “shameless” tone of voice that allowed me to tell what had happened at the top of my lungs, without thinking about “what people will say”, even if something happened to me. It was my shield.

ROSE IN THE MOUTH

Berlin, my father: “May God bless those who invented WhatsApp and the camera phone. When I miss you, I call you immediately, I see your face and it’s a breath of fresh air for me. Sometimes my heart constricts, I can’t breathe. After seeing you, the blood rushes back to my heart, my nostrils open, my lungs breathe again”.

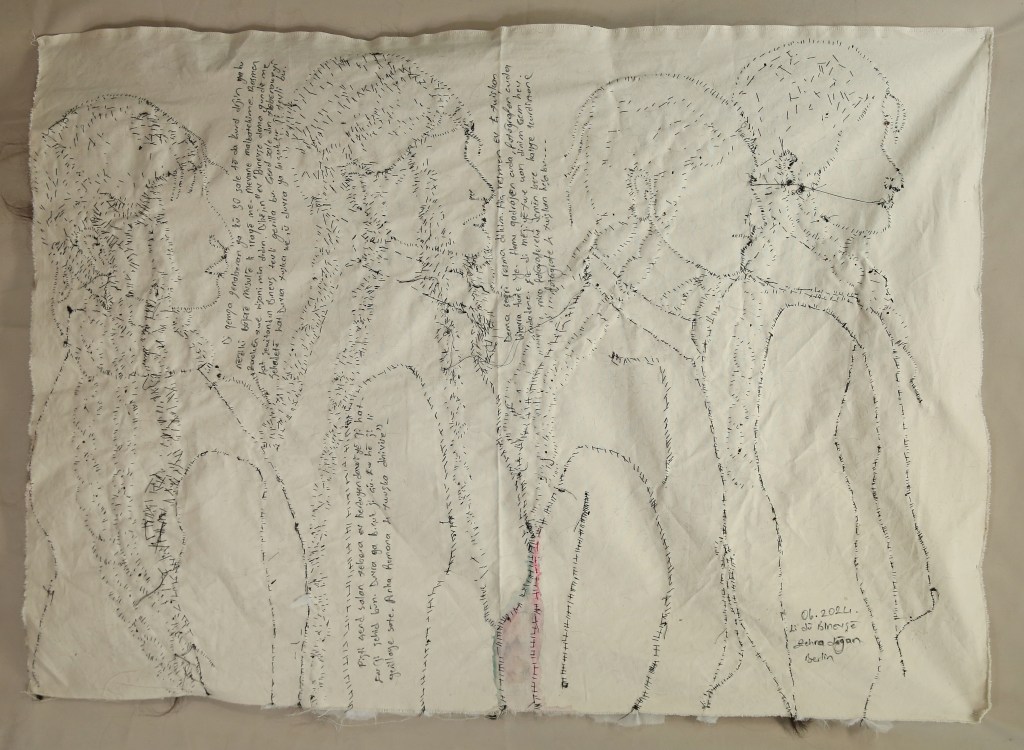

AFTER BINEVŞ

I am in the Maxmur refugee camp near Mosul, Iraq, where Kurds live. In the part of divided Kurdistan that was given to Turkey in the 1990s, the Turkish army burned 40,000 Kurdish villages and forced the population to leave. Some people came to the Iraqi part because their villages were close to the border. They said every year, “This year is the last year, everything will end and we will return home”. 30 years have passed and they are still waiting…

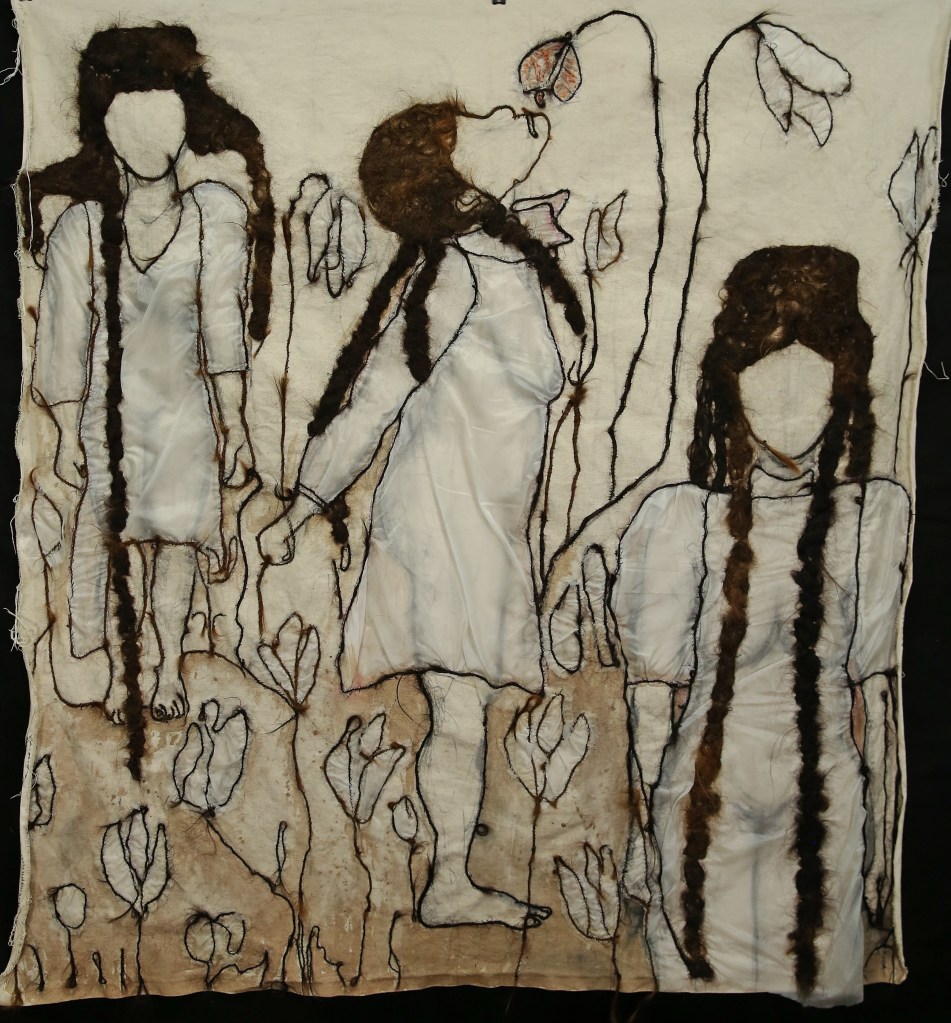

I am invited to a family’s home. They showed me photographs. One of a young woman called Bınevş (which means “wild pansy” in Kurdish). Years ago, when her village was burned by the Turkish army, she joined the guerrillas. She was killed there shortly afterwards. Then her two sisters followed the same path. They also died. The fourth sister also joined the guerrillas. She is now writing her story. There are no photographs of the four sisters together. I see each of them in a different photograph. I put them together in my mind. In my imagination I put them next to each other, like in a photograph of Kurdish girls taken by a European photographer a long time ago.

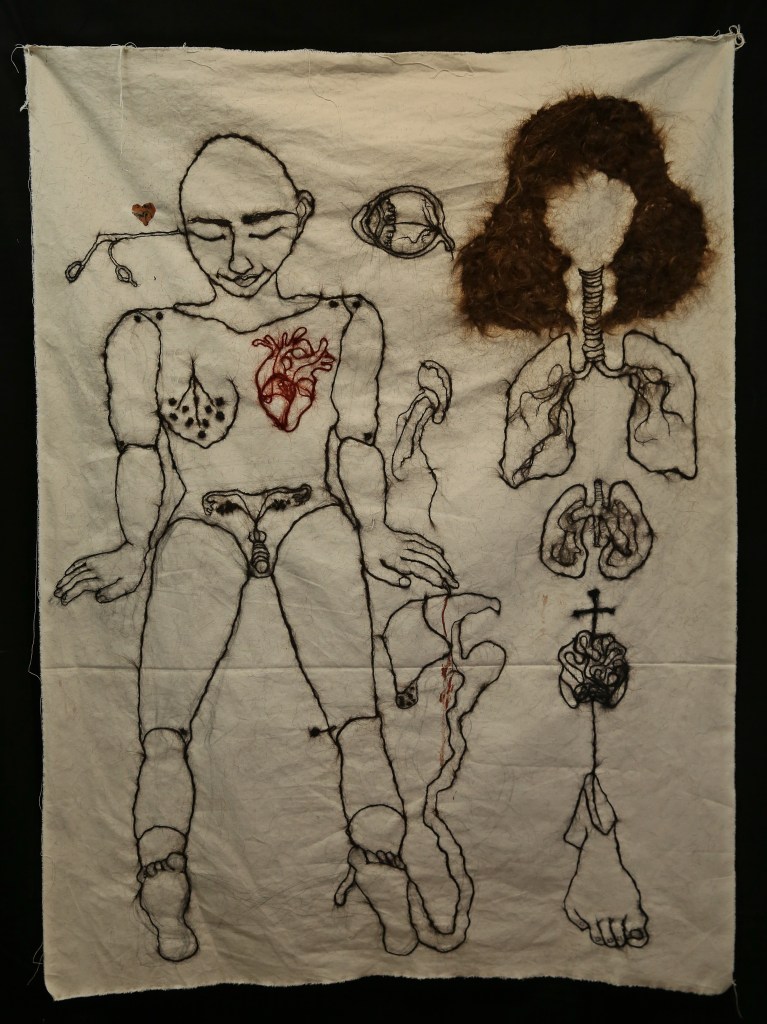

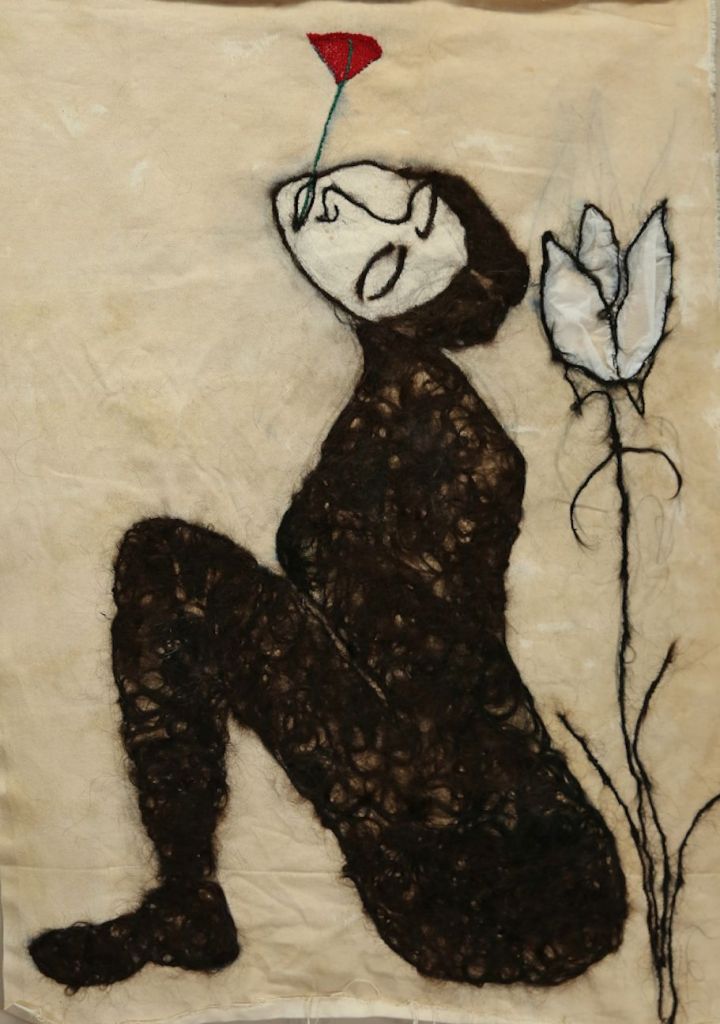

THE DEAD BRIDE

Telephone conversation with my mother.

My mother: The work behind you is very nice. You use hair very well. And the red, is that menstrual blood?

Me: Yes, it is menstrual blood.

My mother: Since you are not yet 18, the sins you commit are not written on my tablet. I am obliged to warn you. I am at peace knowing that your sins will not be imputed to me. So I say this for you. But I am sure that your sins will not be imputed to me. I say this for you. My father and his scholar friends at the madrasa once told me this: “Even for a man to see a woman’s bloody menstrual pads is a grave sin. As serious as a woman giving birth to a bastard. When you were in prison, they denied you your materials, they put pressure on you, and that’s why you found this way. I gave you the greatest support. I brought you cloths as if I was giving you clean clothes to paint, and I smuggled your paintings with my own hands. But now you are out, you are free. You have millions of choices of materials. There is no reason to keep using menstrual blood.

Me: It’s my way of expressing myself. Industrial colors seem strange and unfamiliar to me.

My mother: To this day, no one has seen my menstrual blood. After each use, I washed my towels, very clean, and put them away.

Me: What do you mean, no one has seen it? I recognized yours among the towels hanging on the roof terrace. My uncle’s wife’s towels were all white, and yours were always stained, even though they were always washed well.

My mother: What should I do about it? The blood stain is a difficult stain. Your uncle’s wife had no children. I gave birth to 9 children, and there was always a steady stream of guests at my house. Besides, it seemed more logical to me to buy bread for you with the money I would have paid for the bleach.

Me: I think that makes more sense, yes. But I saw your faded, dull, invisible bastards all the time. They were there and they weren’t there, just like the Djinn. Because they were actually menstrual diapers that were clean and ready to be used again, but they were diapers that had been washed and considered clean, but the stains were still visible because the washing was incomplete. They weren’t absolute stains, but they weren’t completely gone. I think they were Jinn bastards.

My mother: Do you want to go to hell so badly? Then go. You went to prison, I thought you would learn from your comrades and come to your senses. But in vain, you made them like you and used their menstrual blood. You went out and went into exile, I thought you would meet reasonable people and they would tell you that it is a sin, but in vain… And without any restraint, you sell them. In my opinion, even though you are free, by continuing to use menstrual blood in your work, you are weakening the power of your work by being forced to use this material in prison…

War, prison, exile… for the first time in 10 years, my mother was angry with me today.

October 4, 2024 Diyarbakır/Berlin

THREE SISTERS

We were three sisters. It was as if there was a secret garden in the wilderness, created for us by our mother. A garden where we could escape when we were overwhelmed by the unbelievably painful reality of the world. And then I got lost. I could not find my way back to that garden.

Translation Naz Oke, editing Renée Lucie Bourges. Photographies Ulas Tosun