INSTALLATION

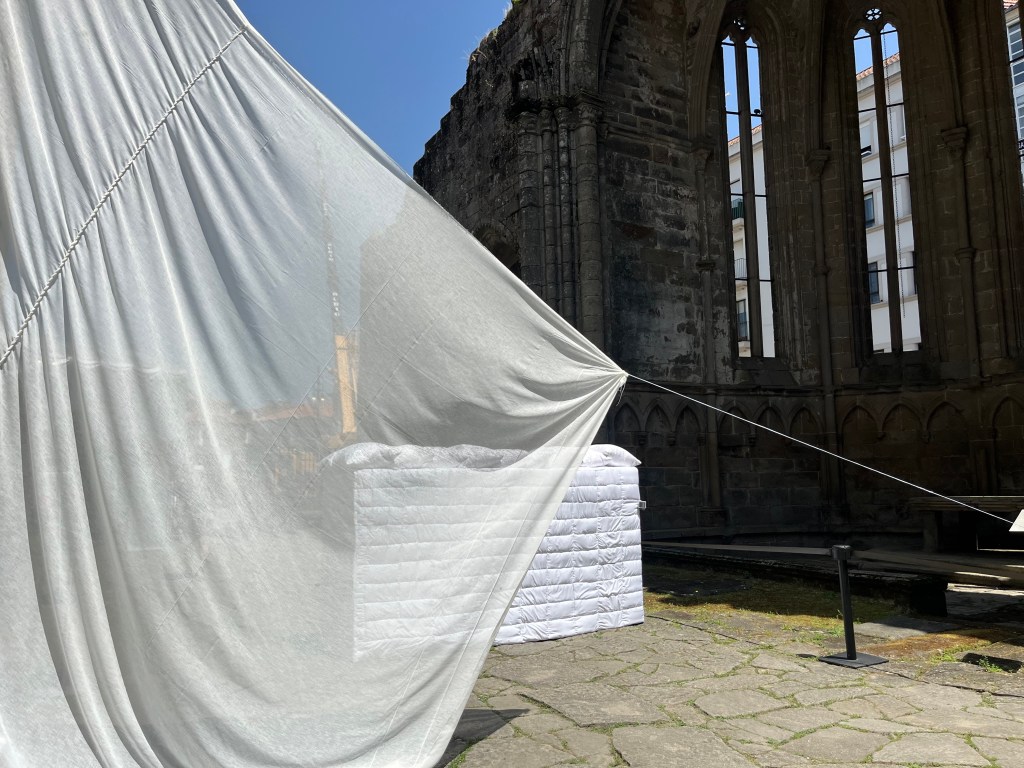

“In this installation located in the Ruins of San Domingos, Zehra Doğan reflects on the struggle to survive in times of violence. The piece focuses on the construction of a barricade, an action that, to the artist, goes beyond a mere physical defence. It stands as a symbol of resistance, of reaffirmation of freedom and the right to exist. The barricade emerges as a response to external aggression and as an act of solidarity, hope and renewal after destruction. In this work, Doğan invites us to question the fragility of human life in wartime and to recognise how everyday objects, deprived of their original function, can be transformed into elements of resistance.”

Anton Castro, Agar Ledo. Pontevedra Biennal curators.

BARRICADE

Zehra Doğan

This text is a compilation of fragments drawn from conversations. about the image of resistance embodied by a barricade, while sewing a quilt and building this barricade over the course of a year, together with the friends who helped me.

In the lands of Kurdistan, I grew up in a small house, but full of people — with nine brothers and sisters, a grandmother, a grandfather, aunts, nephews, and cousins. That’s why Virginia Woolf’s statement about “a room of one’s own” has always felt foreign to me. My room of my own was the quilt I pulled over myself at night— always changing, but creating the same effect.

That quilt, which I shared with my sister and my older brother since we slept on the same mattress, was not entirely mine. To create a space that belonged to us, like all children who probably grew up in conditions similar to ours, we developed a strategy based on our bodily movements under that shared quilt. By pulling it over our heads in a fetal position, tucking part of it under our feet, between our legs, or under our buttocks while pushing with our elbows, we had developed, at that time, an ability to create, within that shared quilt, a private space that belonged to us only.

In a space where solitude was impossible, it was only with that quilt that we could enter our imaginary world, our personal space, and create a private universe, and I still live that way today. For example, even in Europe, where I have been living in exile since 2019, I still don’t have a space that truly belongs to me. No matter where I am, even when I am given a room of my own, it is only after I pull the quilt over my head and position my body in certain ways that I feel inside that room I have carried with me since childhood.

This bond I developed with the quilt likely comes not only from the fact that I am from a large family, but also because I grew up in a region far removed from the classic forms of “intimate spaces” offered by the modern world. Yet, even as times and places change, the quilt remains my most familiar, safest, and most intimate refuge, because it can be found anywhere. In a home where intimacy was not built through architecture but through the limits of the body, my personal room of my own has always been this quilt that I pulled over myself. The relationship I built with a mobile blanket rather than with a fixed room must, in fact, have been an attempt to create a space in its very absence.

Life in the house where I grew up was a form of communal living. Our personal belongings and private spaces were very limited. This also meant that we encountered the idea of ownership quite late. But my strong desire to realize my dreams led me to create spaces of my own within the house itself. In the summer, I managed to build shelters, cities, secret streets: at the top of a tree; in the autumn, under the dining table that we never used; in the winter, under the quilt. My insistence on not folding up my mattress had been resolved through an agreement with my mother. As soon as I finished my breakfast, I would slip under my quilt, close my eyes in the magical atmosphere created by my room of my own, and surrender for hours to my dreams and my imaginary world. This situation lifted me out of the poverty we lived in, and from the harsh reality of a world dominated by war. In the imaginary world I created under the quilt, I could live as I wished.

The fact that my family accepted the spaces I created and considered them as part of the house was not easy. I think that constantly pulling this quilt over myself, transforming it into a tool of my own life, eventually came to be accepted by the other members of the household, and the matter was settled with a simple: “Zehra is like that.”

The quilt was in fact a barricade between my family and myself, between the world and myself. Thanks to this barricade that I built with a very fragile, easily destructible material, I proclaimed my autonomy. It allowed me to feel happier and safer in that house. Sometimes, I was seen as a strange or even as a crazy person, but being accepted as I was strengthened my bond with life. As long as I existed in my own world, I found, in my own way, a means to exist in the outside world as well.

Today, in my state of wandering, without a homeland or a place of my own, far from my country, the quilt is undoubtedly the object that brings me the most comfort. It is like a teleportation device that takes me on a journey to an imaginary world of my choosing, far from the reality of life, which can sometimes be too emotionally heavy to bear. It is also a barricade under which I can take refuge at any moment, in places or times where I do not wish to be.

I sometimes wonder: if I had experienced the opposite of what I knew at that time, who would I be today? What would my memory, my sensations, my personality tell me? If that quilt had been suddenly pulled off me, if my refuge at the top of the tree or under the table had been destroyed, and if I had been punished for what I was doing, what damage would my being have suffered, and what path of existence would I have had within that family?

Barricade: From Intimacy to Public Resistance

As I gradually witnessed, in the lands where I grew up, how quickly public space — the street, the square — could be militarized, the protective relationship I developed with the quilt transformed into something else: a barricade.

Barricades are fortresses erected to survive and defend one’s spaces. A central form in the history of revolutions, they are a powerful symbol of major uprisings, not only on a physical level but also on a metaphorical one. The barricade is a defensive architecture born from the simple repurposing of available objects — chairs, armchairs, bags, stones, trees, wheels, doors — which were not created for that purpose. Taken separately, each of these objects carries a different meaning; but once assembled, they become a unified form of resistance and one of the most striking images of social struggles.

The many barricades erected in Paris during the Commune in the 19th century, in Spain in 1936, in Germany in the 1940s, or in Latin America and Paris in May ’68, are all examples of everyday objects being transformed into defense devices, diverted from their usual purpose.

An armchair placed in the middle of the street, taken in isolation, creates a strange image, but once combined with other objects, this strangeness disappears: because it is no longer an armchair — it is a barricade.

The barricade, which is not based on any professional architectural plan nor on a ready-made kit, is born from the direct intervention of the masses. This is precisely wherein its strength resides: an alternative form of defense created by the people’s shift from the horizontal to the vertical, in the face of the vertical power of state violence. Stones are torn from their place, streets are reshaped.

Peace, Resistance, and Life

In 2013, when the Islamic State organization was attacking Kurdish villages in Shengal, Iraq — killing thousands of people and capturing five thousand women — I went there as a journalist to cover the events. That’s where I encountered barricades. Similarly, during the conflicts that took place between 2015 and 2016 in the Kurdish regions of Turkey, the barricades — which until then I had seen as merely a form — became a part of my life in the areas where I was reporting. For almost a year, I had to hide behind these barricades to protect myself from the weapons of soldiers and police officers, or from potential attempts at arrest.

Even though I knew that these barricades, built to protect against state-of-the-art military vehicles, were in fact very fragile — what made me, like everyone else, seek refuge behind them? Why did these barricades, despite their vulnerability, inspire more trust than military armor? In addition to having been erected for physical protection, did these structures also carry another message? Why did thousands of people stubbornly place such forms in the streets, fully aware that they would be destroyed?

This form, suddenly born from the despair of an unarmed person — although for a defenseless civilian building with bare hands, it appeared harsh and solid due to the stone — for a soldier in an armored military vehicle, it was merely a “heap” to be eliminated, a task as easy as playing PlayStation. And that is exactly what happened at times. The fact that the shape of the barricade could be defined so differently depending on each side’s point of view sparked deep interest in me.

The period during which I was in close contact with the barricades coincided with a time when, in the Kurdish region referred to as “Eastern Anatolia” or the “Southeast of Turkey,” official security forces were carrying out violent attacks on cities. The “peace process,” initiated in 2013 between the Turkish state and the Kurdish movement, had come to an end, and the relatively optimistic and peaceful atmosphere gave way to a chaotic climate marked by horrifying scenes of disproportionate violence. The nationalist and authoritarian political discourse that began to dominate the state brought the peace process to a halt and gave rise to an undeclared state of war across the vast Kurdish region.

In response to this situation, the reflex of the Kurdish people was a form of civil disobedience: self-governance, which encompassed democratic and rights-based demands. This model aimed not only at recognition of the Kurdish people, but also of all religious and ethnic identities in the country. It proposed a way of life that was ecological, libertarian, and based on gender equality. The State chose to suppress these demands through classic methods of violence. By declaring a state of emergency, it turned a context of peace into one of total terror.

Bomb attacks were carried out during peace rallies (Ankara, Suruç, Diyarbakır in 2015). In Kurdish cities, a real state of war was established, with arrests, detentions, raids, and the heavy bombing of certain neighborhoods, which were reduced to rubble. Thousands of people were imprisoned, and thousands more were forced into exile. In the face of these attacks, Kurdish communities began to erect barricades in their towns as a means of self-defense. The curfews, frequently imposed for over a year, completely disrupted the flow of daily life. Some neighborhoods were placed under blockade, and a total siege atmosphere was established with the help of armored vehicles. To meet their daily needs and simply survive, the population found no other solution than to erect barricades. In areas where stepping into the street was equivalent to a death sentence, many people — children, the elderly, or the sick — were crushed under armored vehicles or shot by sniper bullets, their bodies left for days in the middle of the street.

Crowds tore up paving stones, took curtains down from windows, brought blankets out into the street. All these everyday objects took on a new function: they no longer made life easier — they saved it.

A large part of the weapons used during these attacks had been imported from European countries.

Despite the massive destruction and the atmosphere of terror that followed this resistance, the barricades allowed many people to stay alive for a long time.

Children’s relationship to the barricade became a kind of war-game metaphor. Faced with curfews that lasted for months, children found various ways not only to survive but also to have fun. The photo below captures a moment from one of these games. To get from one street to another, they would first check — using makeshift periscopes placed at the end of the barricade — whether there was an armored vehicle at the corner. And thus, with the ingenuity unique to children, they figured out how to cross from one street to the next.

In the end…

The barricade, as a form, disrupts the ontology of objects. The armchair is no longer meant for sitting, but for protection or hiding; the stones (cobblestones?) are no longer used to build a road, but to block it. These insignificant materials from daily life are once again mobilized to ensure the survival of life.

Even today, thousands of people cannot return home, simply because they no longer have a home. There are still missing bodies, still tens of thousands of people in prison. The pain, the anger, and the memory of that time remain vivid. But the barricade was the direct response produced by the people in the face of these attacks. This form erected in public space went beyond intimacy: it was the expression of a collective resistance. And that expression continues to resonate. The barricades were the epic transformation of those worthless objects into a powerful image.

Of course, those who built the barricades also knew that a barricade would remain fragile in the face of bombs, that it would collapse quickly. But for them, the barricade was not just a means of physical protection: it was also a metaphor for existence. To oppose, with a simple form, the powerful images of authoritarianism and militarism (tanks, cannons, etc.), to refuse submission, to defend one’s own living space. If the shape of the barricade appears rectangular, rough, and hard, it is undoubtedly because of the image of the blanket from my childhood, whose form, in my memory, evokes a feeling of softness. Like me, many children have experienced the possibility of a plural life under a single blanket. Inspired by Judith Butler’s theory, which sees vulnerability as a form of shared existence, this blanket-barricade is particularly open to the vulnerability of bodies that, throughout history, have been devalued, erased, or rendered invisible. In this sense, the barricade is both a space of exposure and of shelter. It resists not by pushing away, but by enveloping; it does not scream, it absorbs.

This echoes the moment of “feminist rupture” described by Sara Ahmed. The moment when gentleness can no longer bear oppression, and thus draws a boundary. In this barricade, gentleness is not a withdrawal, but a refusal built with tenderness.

There is a call here to reconfigure the politics of space by freeing it from rigid geometries and masculinized architectures. The quilt, traditionally linked to the domestic sphere, to intimacy, and to a form of collective production, carries within its fibers a historical memory. In this work, it becomes a political subject: it breaks down the public/private dualities and reveals the aesthetics of care as a tool of resistance.

The quilt-barricade stands as a silent monument both to collective fragility and to resistance woven into gentleness. It does not yield to the spectacle of virility that power demands from resistance. Instead, it takes its place in space through textile, through bodily and relational softness, thus redefining what a barricade can be.

The Stones of the Gentle Uprising: The Space Behind the Barricade

I erected my barricade at the heart of the Santa Domingo church. This choice was no accident. For the history carried by this place resonates with my practice of the barricade.

Once a church, it was later wounded by war, bombed. Its destruction was proposed, and the people opposed it. It was then decided that its stones would be dismantled to build roads, and again, the people refused. These stones, even though they belonged to a now-desanctified faith, were deemed worthy of preservation.

Today, it has neither congregation nor religious order. And yet, despite the loss of its original function, the church was preserved, becoming the support for other uses: a women’s prison, a public exhibition space… As long as the stones of this religious edifice remain in place, anything becomes possible.

The essential question to ask here is this: What is worth protecting? When, and for whom, does a stone, a structure, a belief hold value?

In my homeland, in Kurdistan, during the curfews, roads lost their function. No one could walk on them anymore. But these stones, rendered useless, were reinvested with new meaning: they became barricades. Civil defense structures erected to protect against state violence. Their uselessness was transformed into “spaces of survival.” Women and children broke open drainage channels to create periscopes; they built underground networks, communication systems running across rooftops. For us, the barricade was the architecture of a dream of autonomy, at the very heart of destruction.

Behind the barricade lies a space to be preserved; but this preservation is not mere defense — it is a proposal for a counter-space.

Those who enter are welcomed by a video: archival images of women and children building the barricades. These collective structures, erected against silence, violence, and obliteration, offer today’s viewer a different kind of spatial experience. The rear side of the barricade becomes a welcoming, hospitable place — a space that includes and envelops.

There is a hole in the front face of the barricade. Those who look through it do not see the rear side, but rather the outside — the front. The photograph framed in this opening freezes a moment: a child, in wartime, looking out through a bullet hole in a wall. The child looks — but what he sees, we will never see. This image acts as an inverted mirror. In an exhibition space in Europe, as we look at a child from elsewhere, we can only imagine what he sees: destruction, fear, another face. If we are not behind the barricade, we can only see the child looking — not what he is looking at. What he sees can only be felt by crossing the barricade.

The optical structure, inspired by the periscope made by children from drainage pipes, is placed just to the left of the barricade. It allows the person behind the barricade to see the front. This structure emphasizes that someone deprived of a home holds not only the right to defend himself, but also the right to see and to bear witness. Thus, the barricade does not exist solely for protection, but also to see the other side, to understand, and even to transform. It replaces the blind gaze that enables summary executions with a reciprocal gaze: a gaze that sees and is seen.

According to Edward Said, exile is not only a physical separation but also an intellectual distance. A person deprived of shelter is neither fully inside nor entirely outside. This in-between state holds the potential to see the world with a fresh perspective, to deconstruct the myths of belonging. My presence in this space also lies at such a boundary: I do not belong to it, yet I am not entirely foreign either. And it is precisely this liminal position that allows me to propose another reading of space: that of the possibility of a barricade woven by women, within the very heart of patriarchal history.

My barricade confronts what is traditionally meant to be protected — faith, structure, the sacred — with what must be protected to survive — the body, memory, the commons. The stones of the church remained in place, and everything became possible. The stones of the barricade, by contrast, were torn from the ground — and from them was born only one thing: resistance. Today, these stones and these fabrics add another story, another woman’s voice, to the memory of this place. Like the invisible barricades of women, this barricade is woven from textile, silence, and gaze. It unfolds not from the outside in, but from the inside out. The barricade is no longer a line of defense; it becomes a stage for memory, for collective resistance, and for a gentle autonomy. I, at the very heart of this work, am neither from here nor from elsewhere, but in this non-place, I open a space — not to protect myself, but to bear witness and to survive together.

The barricade is a material translation of the non-place and the absence of home. Just as Edward Said defines exile not only as a loss but also as a way of thinking, this barricade is born of that displacement. The comforter, which at home protects and envelops, becomes here a border-object — a temporary barrier or shelter. In this way, the barricade includes as much as it excludes — like exile, it occupies a suspended position between belonging and rejection. The comforter, symbol of warmth, becomes here an armor of resistance; the home transforms into a geography that moves with the body. And again, Edward Said, for whom exile is both a devastation and a singular mode of thought: the exile never fully belongs to one place, and it is precisely this condition that prevents them from sacralizing it or becoming fixed within it.

The loss of belonging opens a critical space. My presence in this place is grounded in such a position: I do not belong to this church nor to the historical codes it carries, but it is precisely this absence of rootedness that allows me to produce new meaning within it. The barricade I weave with the memory of women, exiles, prisoners, and children offers a counter-voice — gentle yet resistant — to the patriarchal history of this architecture. Edward Said’s phrase, “even far from home, you carry it in your memory,” takes material form here in the memory of the duvet. The barricade is no longer simply a line of defense; it becomes a collective space built from the memory of those torn from their land. Each stitch, each fold becomes a testimony to that displacement. This barricade does not only block; it also opens a passage, constructing a new place of belonging.

This barricade brings to a place marked by the wars of the past a new form of struggle, gentle but insistent, intimate yet collective, invisible yet persistent. It is not a barricade that rises from the outside in, but one that unfolds from the inside out. Not to protect, but to bear witness, and to survive together. It is the barricade of those who want both to hide and to be seen, to protect and to see. It is the barricade of those who think of art as a home, or as a place of resistance, for those who cannot return.

PRODUCTİON

Zehra Doğan

Sevimgül, Steeve Casteran, Naz Oke, Refik, Afat Baz, Ozgür Rayzan, Nerea Lores Acuna, Fatima Cobo Rodriguez, Carlos and his team.

Curators: Agar Ledo, Anton Castro

Thanks to: Wenda Koyuncu, Erden, Maral, Yunus, Hülya Dılo, Berfin, Yavuz, Özgür Reyzan, Afat Baz, İda Pisani, Jineology Academy and Kurdish press workers and my family…

English translation Lucie Bourges

Version en français